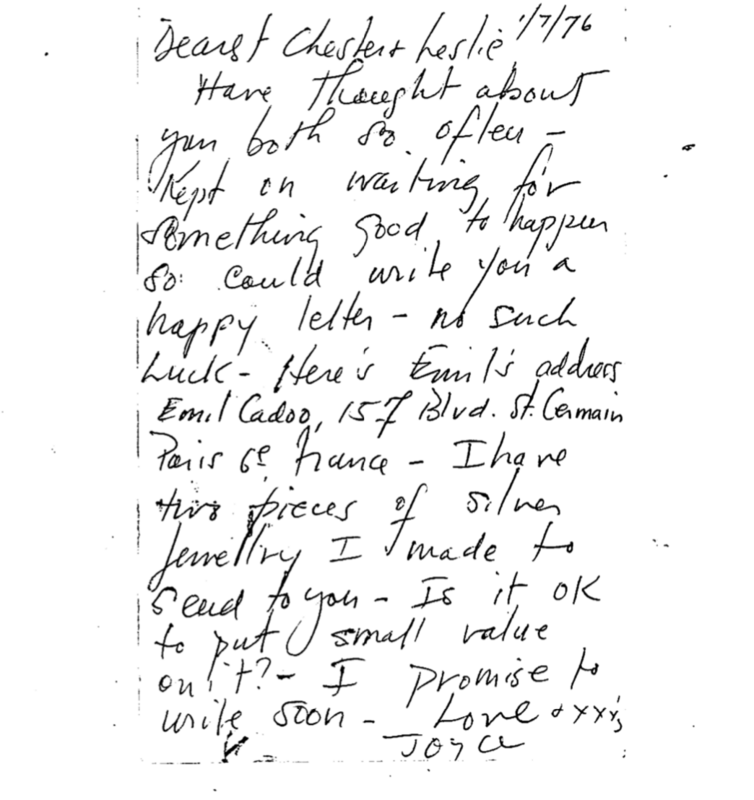

We talk a lot about identifying the unidentified in the archive. So we thought we would show you an example.

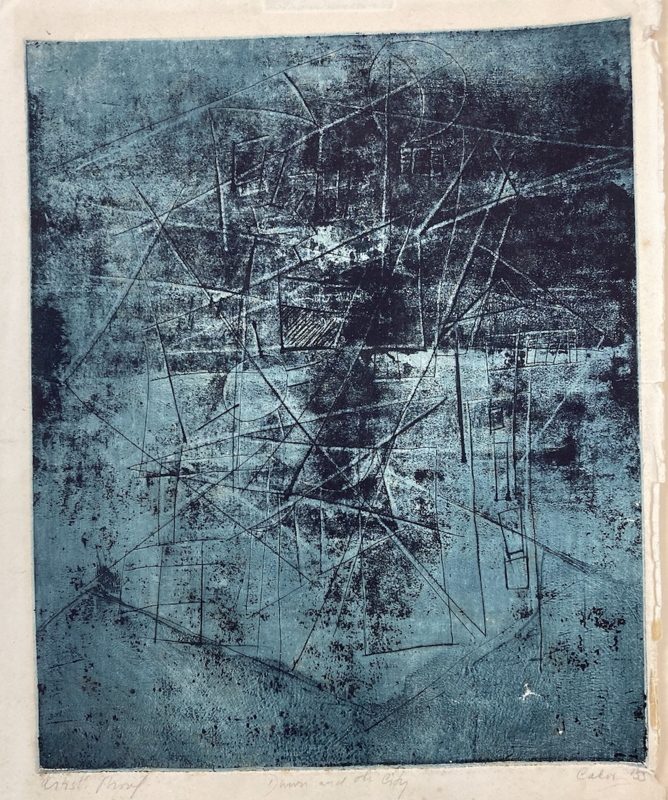

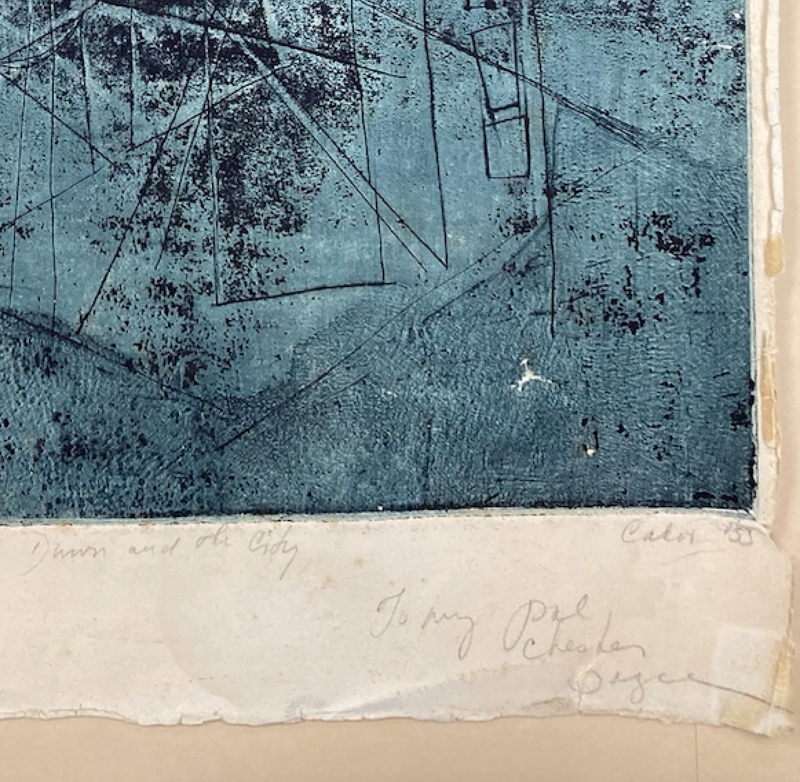

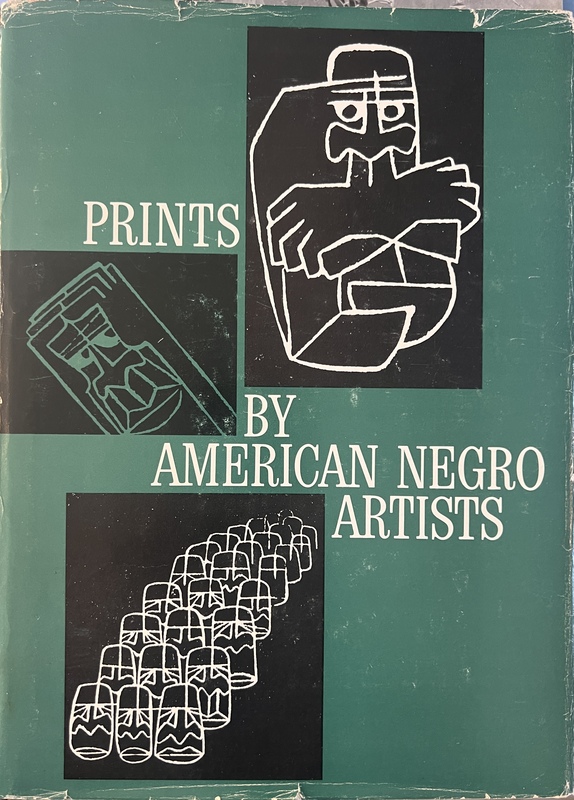

This etching is in the Chester Himes papers at Amistad Research Center in New Orleans [fig. 1].

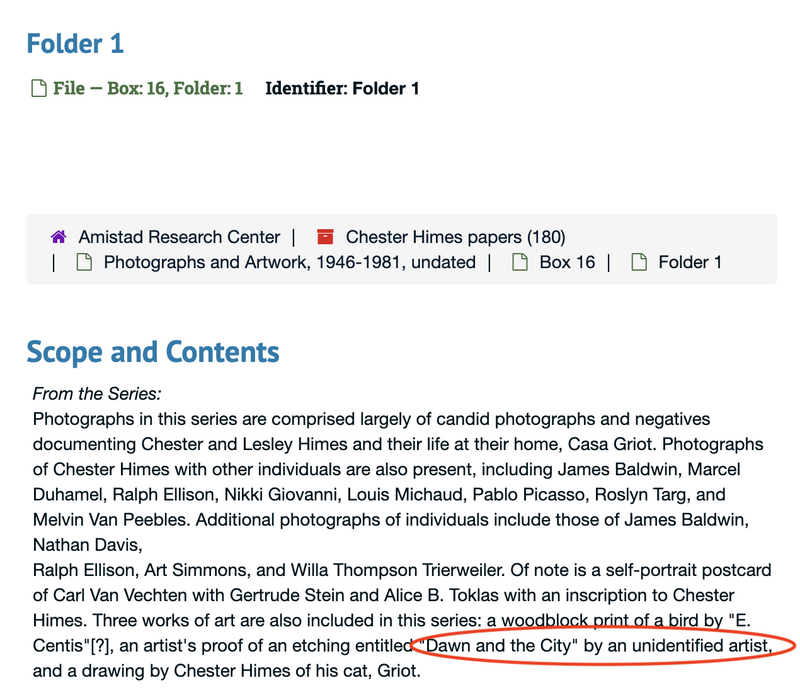

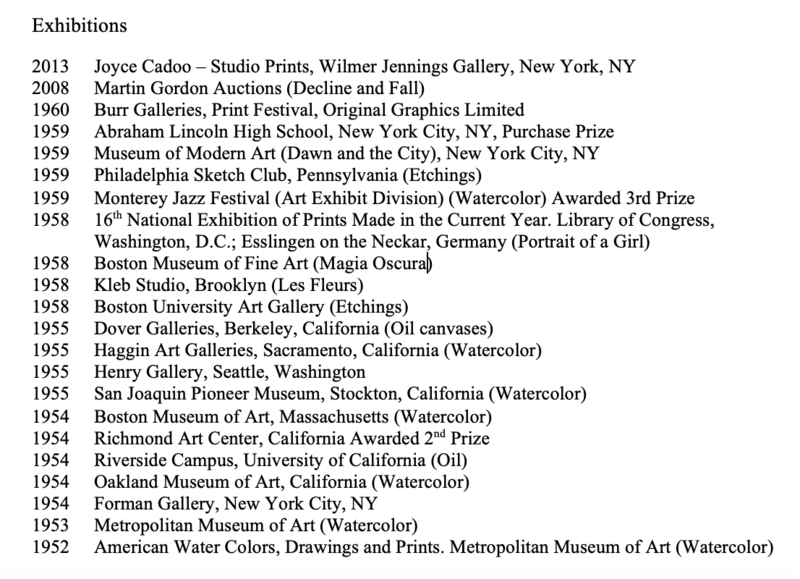

When we first learned about this etching we only knew its title. The finding aid gives that –“Dawn and the City”– but states that it is “by an unidentified artist” [fig. 2].

A finding aid is an index to what’s in a collection. Figure 2 shows this portion of the Chester Himes papers finding aid. You can see a lot of names here (James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Nikki Giovanni), but when the name is unidentified, the person is invisible.